Investing in mutual funds involves paying a number of fees. Some of them are paid directly, others indirectly. Most of these fees are paid to the fund manager. The rest are given to the broker through who the transaction was completed.

When an investor considers joining a mutual fund, he should take in to mind the fees he will have to pay. While these fees may look marginal at first glance, their cumulous affect over years can be significant.

There are two types of fees:

- One-Time Shareholder Fees.

- Annual fund Operating Expenses.

Each of these types is divided into several parts, which will be detailed below.

Shareholder Fees

The shareholder fees are charged according to the following categories:

- Front-End Load

The front-end load is the one-time payment that is made when purchasing shares of a mutual fund. The fee is calculated as a percentage of the investment. By law, the fee can not exceed 8.5%. For example, if an investor puts down 10,000 dollars, and the front-end load amounts to 4.5%, then 450 dollars of the 10,000 is handed over as fees and the rest is invested. The fees collected at this point are never returned to the investor.

- Back-End Load

This fee is paid when an investor redeems his shares of a mutual fund. It is calculated as a percentage of the value that he is redeeming. Generally, the fee becomes smaller the longer an investor has held shares in the fund.

Most funds have only one of these two types of fees.

Annual Fund Operating Expenses

The annual expenses are paid automatically to the fund manager from the fund’s assets. This money is meant to cover the expenses involved in managing the fund.

The operating expenses are made up of the following fees:

- Management Fee

The management fee is the main component of the operating expenses. The management fee is a payment to the fund manager in return for the professional and administrative services that the manager provides. They are calculated as a percentage of the fund’s assets.

- Distribution Fee

The distribution fee, also called the 12b-1 Fee, is meant to finance the marketing and distribution costs of the fund. The law caps this fee at 1% of the fund’s assets.

- Other Expenses

The fee for other expenses provides for services such as providing information for shareholders, maintaining a website and other miscellaneous costs that arise. This is also calculated as a percentage of the fund’s assets.

Not all funds collect fees from all of these three categories. Each fund is free to choose how much it will collect in each category or not to charge a fee at all.

Two Kinds of Mutual Funds

In the US it is possible to differentiate between two kinds of mutual funds:

- No-Load Funds, which don’t carry a back-end or front-end load.

- Load Funds do charge fees when entering or exiting it.

In recent years, the number of no-load funds has expanded considerably.

Expense Ratio

The expense ratio calculated the total fees that are charged as a percentage of the fund’s assets.

Example:

- Management Fee: 0.75%.

- No Distribution Fee.

- Other Expenses: 0.22%.

The expense ratio is 0.97% (0.22+0.75).

Fund Prospectus

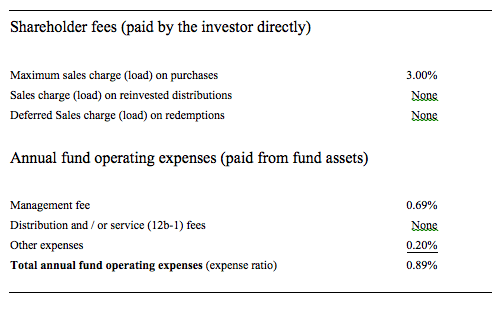

The mutual fund’s prospectus details the fees that it charges. Funds are required by law to include a table, in a clear, uniform style, with all of the fund’s fees. This is called the Fee Table and it is the most reliable source for information on a fund’s fees.

This is an example of a load fund’s fee table.

Fee Table

Numerical Example

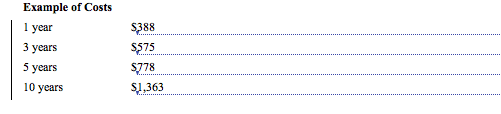

In addition to the fee table, each mutual fund must present, in a uniform style, a numerical example of the fees that are charged. The example is always of what will happen to an investment of $10,000. It lists the cumulative fees that the investor will be charged after one, three, five, and ten years. The fees are calculated assuming the fund has an annual 5% yield and that the investor sells his shares after ten years.

Here is an example:

The Importance of Fees for an Investor

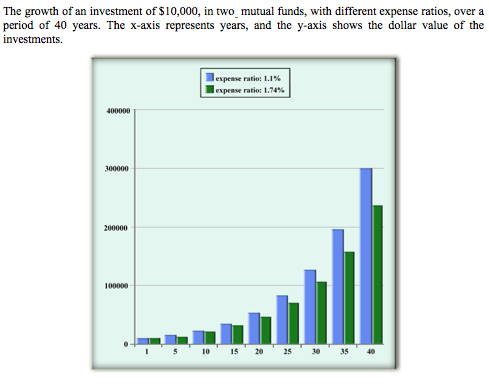

Despite their marginal appearance, it is important to emphasize that they can be very important over time. The following example demonstrates this.

In both funds, A and B, $10,000 is invested. They both achieve an annual yield of 10%.

- In fund A, the expense ratio is 1.10%.

- In fund B, the expense ratio is 1.74%.

After 40 years, the person who invested in fund A will now have $302,771, and the person who invested in fund B – $239,177. That’s a difference of $63,594!

Diagram 34 presents the differences in the investments in these two funds over the entire investment period.

Diagram 34